On June 23, 2019, IPSI hosted several International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP) participants from around the world. The program was centered around participants combating violent extremism in their respective countries, and the all-day workshop focused on community-based approaches to countering violent extremism (CVE). During the first session, the group defined and differentiated CVE and preventing violent extremism (PVE) in order to establish a framework for future sessions.

Following the open group discussion, Nick Marinacci, the Director of Political Transitions Practice Area at Creative Associates, offered a practitioner’s perspective about CVE. He outlined five themes throughout his discussion. Firstly, at the community level, the distinction between CVE and counter-terrorism (CT) is not as vital to the process. Secondly, it is critical to outline the drivers of extremism and radicalization. Thirdly, in CVE work, legitimacy matters as much as capacity. The most effective strategy of community building involves finding leaders and other individuals recognized by the community and building up their capacity. Fourthly, the significance of marketing and communication. CVE work is inherently political and a battle of ideologies, and as a result, one has to convince the population that the CVE mission is better than the alternative. Lastly, regarding methods of measuring success, Marinacci stressed measuring success through contribution, not attribution, based on the environment that the work is taking place in.

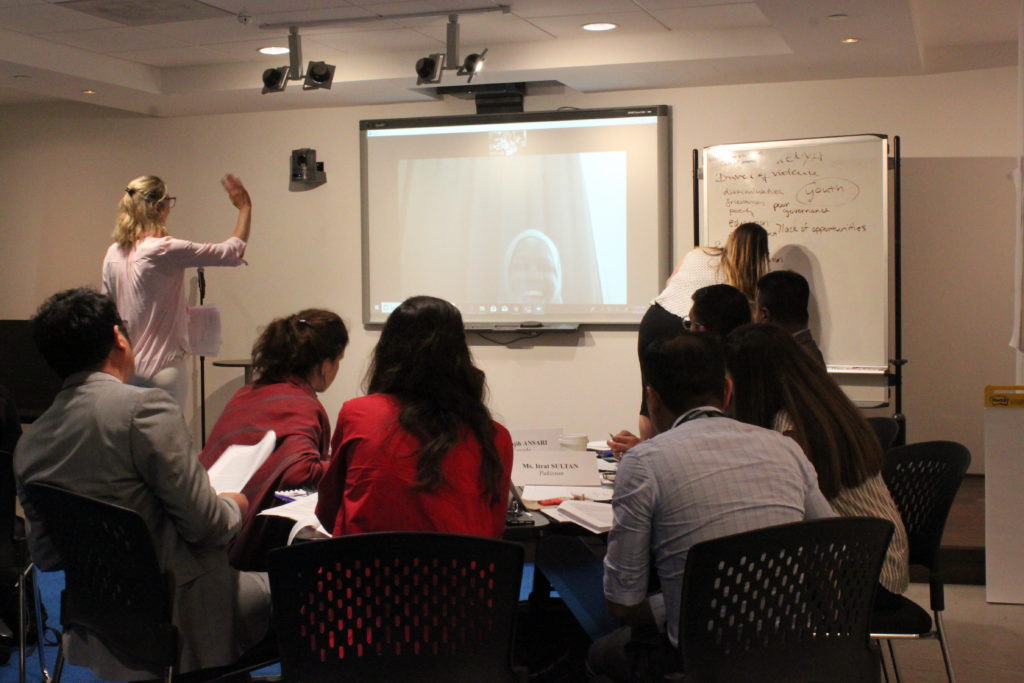

Afterward, Rehema joined the group via Skype in order to expound on the Kenyan case study the participants were given. The case was chosen in order to analyze and discuss the drivers of violence and key issues in Kenya. Rehema further discussed the national terrorism strategy in Kenya and how it impacts the CVE work that is implemented domestically. She concluded with emphasizing the relationship between members of the community and the government in order to successfully implement programming.

Divided into groups of four, the participants in each group were assigned an actor for a role-play exercise. The four roles assigned were law enforcement, civil society, religious leaders and government. This role-play was an exercise in collaboration amongst different groups within a country. The second activity of the afternoon centered around identifying how gender affects CVE work. Deborah read statements and instructed the participants to move to the appropriate side of the room based on if they agreed or disagreed with the statement. After the participants decided on their places, there was time delegated for discussion in order to flesh out the ideas and reasoning for their placement choice in the room. Relevant statistics and reports were given in order to supplement the anecdotes of the participants.

A panel of experts concluded the activities of the day with a discussion about approaches to community CVE strategies. Dr. Pauline H. Baker shared her academic and practical knowledge, including the efficacy of the Fragile State index. She stressed the need for the development of quantitative data within the field. Ryan Greer from the Anti-Defamation League shared the integral function of counter-messaging in countering white supremacy messaging on the Internet. He described the pyramid of hate: at the bottom are actions that are frequent but not threatening, such as bias. However, if actions are not made to counter bias, it can develop into hate, which can then lead to extremism. Henry Bardridge from the International Center for Religion & Diplomacy discussed the integration of religion and religious leaders in areas of conflict. The participants concluded that CVE is a broad topic in which everyone plays a role and sustainability is key.